Justin Daraniyagala (20 July 1903 - 24 May 1967)

Chapter X

The Painter's Painter

Daraniyagala’s virtuosity

Justin Daraniyagala lived in isolation but that was not what made him eccentric. He took enormous pride in his own judgement and revelled in the certainty of his own craftsmanship. He was not prepared to compromise – nor did he – and that steadfastness was seen by some as obstinacy. He was probably quite aware of all this and enjoyed the privileges that went along with being seemingly unorthodox. At the inaugural exhibition of the ‘43 Group he was seen delivering himself of a lecture on the nature of art for the benefit of one bemused gentleman: Dr G. P. Malalasekera. He indulged in that sort of thing. I recall a visit to him in the splendour of the family estate at Nugedola. Pasyala, when, momentarily distracted from the endless flow of his words, I suddenly found myself being challenged by him: did I not think he could box? Did I not think him capable of knocking the Spaniard off the walls? I mumbled something which Justin Daraniyagala must have taken to be negative. He was on guard in a thrice. Strike him here, and strike him there, he invited me. He gave me some minutes of great trepidation before the pugilist subsided and we went back into talking about Paris and London and life in the village. He made it hard for you not to remember that he had gained the Bantam weight Boxing Blue at Cambridge in addition to having obtained a Law Tripos. All this was remarkable considering that he was very slight of build, extremely thin and looked quite emaciated. Hr smoked incessantly, claiming the while that he was dying of consumption. He had been saying that, of course, from the day he returned from Europe in 1929.

Among other things he hid discreetly the fact that he had been best man to his cousin, the one-time Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike when he married Sirima Ratwatte in I 940, herself later to become Prime Minister of Sri Lanka at the general elections following her husband’s assassination in 1959.

DARANIYAGALA: Girl with Goldfish. Oil in canvas (61cm x 80cm) Anton Wickremasinghe Collection

I first visited Justin Daraniyagala at Nugedola, Pasyala, in the company of Ivan Peries who in his role of guru had required me to drive him there. We met Daraniyagala in his studio, a small cottage some distance from the family mansion – itself a marvellous place, filled with extraordinary treasures, among them a portrait of the historian, Sir Paul Pieris, (Daraniyagala’s father), by Augustus John; drawings by Matisse and Modigliani; Moghul miniatures; Chinese jade vases; South Indian bronzes – a rare collection of truly beautiful things. Three rooms of the small house among the coconut trees were filled with Daraniyagala’s work, huge canvases, never quite finished, ever suspended between the beginning and the end. He treasured these himself and rarely sold any. He would not price them. Stacked in two large tea-chests in the back verandah was a vast collection of Sinhala masks which termites had begun to discover. Sometimes, conspiratorially, he would produce a sketchbook of tissue-thin paper and show us thumb-nail drawings for projects he had in mind. Or a drawingbook of exquisite pen-and-ink or pencil drawings of the men, women and children of his village. A swift glance, and they were soon put away. Also in the studio were ceramic pieces by Daraniyagala. It was a medium he returned to occasionally but never fully exploited.

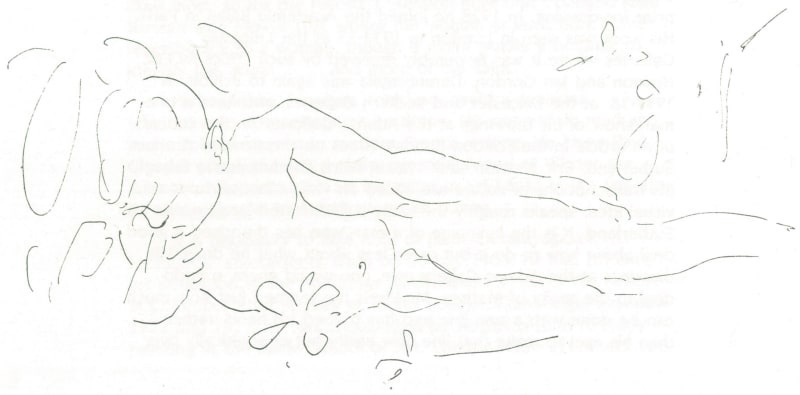

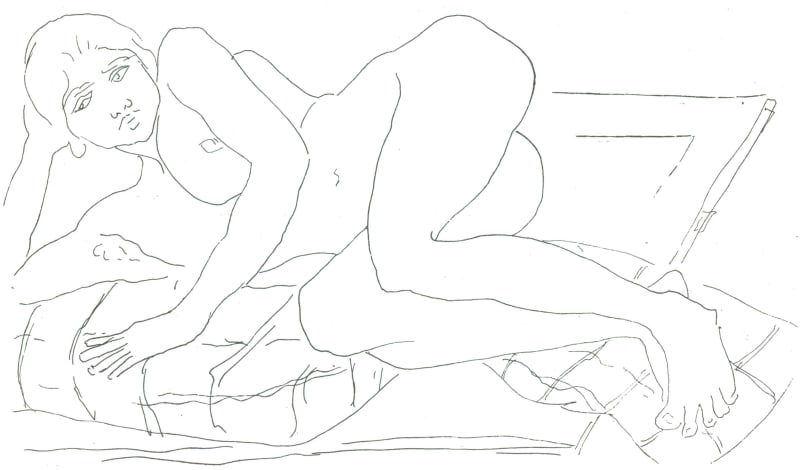

DARANIYAGALA: Pen and ink drawing

On this occasion Daraniyagala spoke about a problem of painting that had interested him greatly – taking the paint to the very edges of the canvas. He argued that most compositions survived on a concentration on the central image or group, but that the picture then falls away at the edges: this he found quite unsatisfactory. A properly educated painter did not allow himself that kind of negligence. Another matter that concerned him very much, he said, was the unseen, hidden side of an object, particularly in the painting of the head as it occurred in portraits. The painter must have a conscious appreciation of the roundness of the head, its other side – the back of the head to properly understand the character of his subject.

For all his concern for the painter’s craft, he was not readily accessible. There was an ambivalence in the response to his work. While he was consistently acclaimed by critics he also had the capacity to disturb. For instance, at the third exhibition of the Group in March 1945. Jayanta Padmanabha, the Daily News critic of the time, found Daraniyagala’s Nude (No 34) “conspicuous among his other canvases as a welcome essay in straightforward painting … I am seldom able to follow what goes on in this same painter’s whimsical pseudo-surrealist nightmares: but I may mention, for the record, an example of his more characteristic moods. No 33 depicts a pale, bored, distorted and apparently decapitated nude falling off a couch while a gazelle-like animal absent-mindedly licks her posterior. This is just a picture within a picture, and the frame containing it is held by a darker figure, also nude as far as one can see, and evidently feeling that felix transitus amoris ad soporem, known to the more profane as ‘complete exhaust’ An irrelevant rosebush grows in the right foreground of the outer frame. The whole is called Composition so one can only suppose it is meant to have some merit as an abstract design.” On another occasion Padmanabha wrote: “You may deplore his nightmares, as I do, but you may not overlook them. At the private view I was asked which of his three entries I liked most: so for the record. I mention here that I disliked least Woman with Flower (19), where the woman at least bore some resemblance to a woman, though it might puzzle a botanist to identify the flower …”; and more of the same.

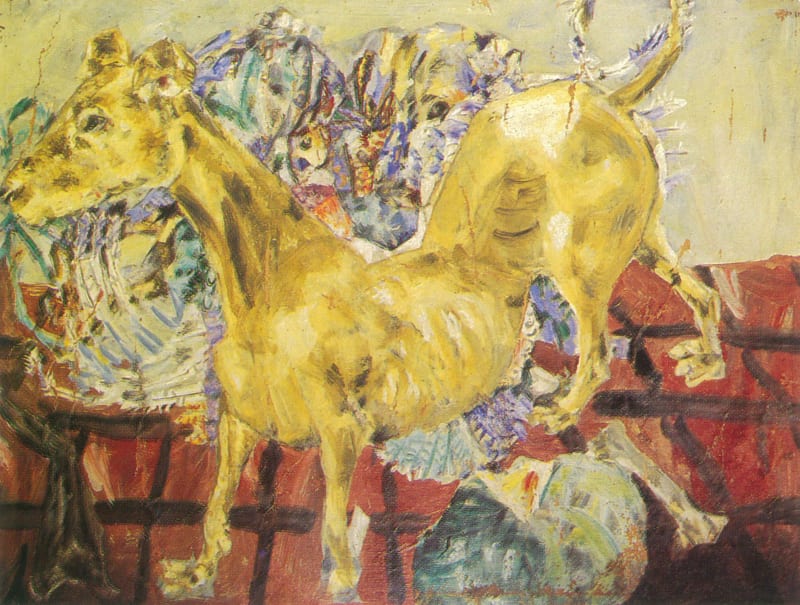

DARANIYAGALA: The Dog. Oil on canvas (c. 120cm x 90cm)

Padmanabha, however, could not avoid a sneaking admiration for Daraniyagala’s erudition. He was widely read and had a special interest in modern French writing. He knew Paul Claude! who had been a close, personal friend of Winzer, the Education Department’s art inspector in Sri Lanka in the twenties to whom Claude! had dedicated two poems. It is necessary to take note of Justin Daraniyagala’s formidable antecedents. Born on 20 July 1903, he had his early art education at the Mudaliyar Amarasekera’s Atelier Art School in Colombo. After studies at ‘Trinity College, Cambridge, between 1922 and 1927, he was encouraged by Augustus John to study painting at the Slade School of Art, London, (1926-27), under two distinguished teachers, Tonks and Wilson Steer. Here he won first prize for drawing. In 1928 he joined the Academie Julian in Paris. His work was seen in London in 1934-35 at the Leicester Galleries where it was favourably received by such critics as Eric Newton and Jan Gordon. Daraniyagala was again to exhibit, in 1937-38, at the Leicester and Redfern Galleries, and have a oneman show of his drawings at the Adams Galleries. In the course of an article in the London Sunday Times on the work of Graham Sutherland. Eric Newton said: “Justin Peiris (Daraniyagala) though his transcriptions of nature are based on visible fact and not on visual idea, speaks roughly the same sophisticated language as Mr Sutherland. It is the language of a man who has theorised a good deal about how to do it but cares less about what he does. His drawings at the Adams Gallery owe, one would guess, a good deal to the study of Matisse. Mr Pieris has learned just how much can be done with a pen line and has trained his hand (rather than his eye) to make that line flow easily but energetically over the paper’s surface. His drawings of Sinhalese girls have a kind of casual eloquence, like a woman’s studied negligee. They are by no means pastiches in the manner of Matisse. Mr Pieris’ line has its own characteristic; it is rapid and urgent; it has more sinew and less elegance than Matisse’s.” There are obvious inconsistencies in this review: the artist, according to Newton, had “trained his hand rather than his eye” but still had a “casual eloquence”; it is “rapid and urgent” … etc. In the Sunday Observer, Jan Gordon said “the drawings and water colours show how cleverly a Sinhalese artist has contrived to adapt hints drawn from Matisse, early Picasso and perhaps something from John, to form a kind of technique which does not too frankly violate an attitude in Art basically Oriental. Within the convention he has adapted, Mr Pieris is a powerful draughtsman.”

DARANIYAGALA: Pen and ink drawing.

S. P. Amarasingham, preparing an article on Daraniyagala for the Sunday Times Illustrated, had this response from the artist to an inquiry: “You ask me from what I draw my inspiration. I should reply: ‘from everything’. You say my pictures are hard to understand: that is due to my incompetence. The painter’s mind is a pendulum which oscillates between the objective reality and a series of imagined variations thereon. The resulting work of art pitches the pendulum closer to one point or the other. The predominance of realism or abstraction limits the accessibility of a work of art to the outside mind.” Daraniyagala was, I think, a true intellectual. He philosophised a great deal in his painting. He discussed many problems. His images were a composite of several observations condensed within one frame. Because of this he appeared to obscure rather than illumine. His work certainly made grave demands of the viewer who could not escape the strength of the statement as it emerged from the paint. Daraniyagala’s enormous experience with the materials of the art made him in Ivan Peries’ description the painters’ painter.

DARANIYAGALA: The Fish. Oil on canvas (90cm x 119cm) UNESCO award. Dr & Mrs Ralph Deraniyagala Collection. Colombo

A note on Daraniyagala in The Studio on April 1954 said: “The art of Picasso in the period of the 1930s is so essentially of non-European lineage that it comes as something of a surprise to find that a Ceylonese follower succeeds in extracting a great deal more of reality from the vision than the great Malagan himself. Maternity of 1947, for example, compared with the latest acquisition by the Tote Gallery, Femme nue dans une fauteuil rouge, contains an abrupt shock of contact with the facts of life which reduced the Spanish work to a voluptuous but withdrawn bourdoir decoration. But Daraniyagala, while submitting occasionally to a foreign style of distortion, nevertheless speaks in the pure language of his own personality as in The Studio, with its richness of colour and lack of depth in composition that recalls, oddly enough. Brangwyn.”

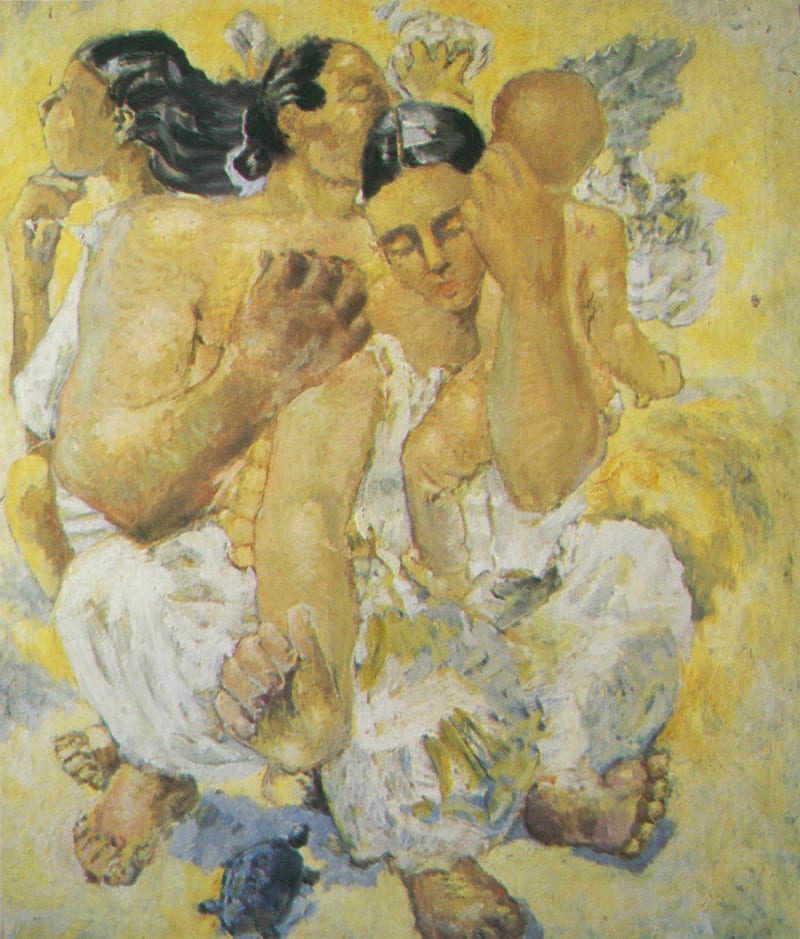

DARANIYAGALA: Three Figures, Baby and Tortoise. Oil on canvas (124cm x 147cm). Mr & Mrs Arjun Deraniyagala Collection

DARANIYAGALA: Pen and ink drawing

DARANIYAGALA: Model resting. Pen and ink drawing

Perhaps the most handsome tribute to the artist came from Donald McClelland in a brochure published for an exhibition of his work by the Smithsonian Institute. New York, some short while after Daraniyagala’s death in 1967. He said that Daraniyagala, having considered the ancient art of Sri Lanka which flourished two hundred years before Christ through to the fifth century paintings of Sigiriya, found in the Buddhist temple paintings of the Kandyan period “a contemplative view of the peaceful and ordinary aspects of life, which had an immediate appeal and stimulus for the aesthetic temperament of Daraniyagala. It indicated to him not so much how he should create as how he should look at the life around him. He was no less aware of the present and of the growing internationalism in all art, yet realised that exterior forces must be considered and reckoned with if his art was to find the right context.” McClelland said: “To a great extent Justin Daraniyagala’s work reflected contemporary life on the island (of Ceylon). With chiselled cogency and finesse, superb balance, delicacy of colour and technique, he conveyed the many facets of Ceylon, its life and its people. In his portrayal, his satire was detached, perhaps a little malicious, yet always forcefully human, pursuing his own philosophies with total disregard of criticism … A philosopher, anthropologist, ethnologist, but first of all an artist Daraniyagala was a visionary, unique for his land and for his time. Power, vision, technique, and profundity – these are the vital elements of any good work of art – and Daraniyagala had them all.”

DARANIYAGALA: Blind Mother and Child. Oil on canvas (122cm x 115cm). Dr & Mrs Ralph Deraniyagala Collection, Colombo

John Berger, sometime art critic on the New Statesman and Nation, was totally convinced of the value of Daraniyagala’s work. He wrote: “Like the Indonesian Affandi, he is an expressionist. Sometimes the work is similar to twentieth century expressionism so far as he simply distorts his subjects to suit his own mood: a process whicb leads to brutalisation, as in his Maternity. But often, as in his magnificent canvas of A Dog (which should be bought straight away by The Tate along with an Affandi), he is able to use the license of expressionism to emphasise and condense associations, fears and hopes that have a far wider validity.” Berger said that in front of such powerful works as Woman and Clown, and Artist and Model. “one rediscovers the paradox that often the heart of tenderness and compassion is violence: the heart of cruelty, timidity.”

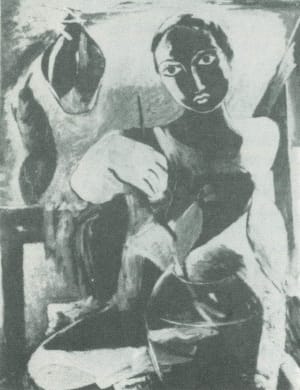

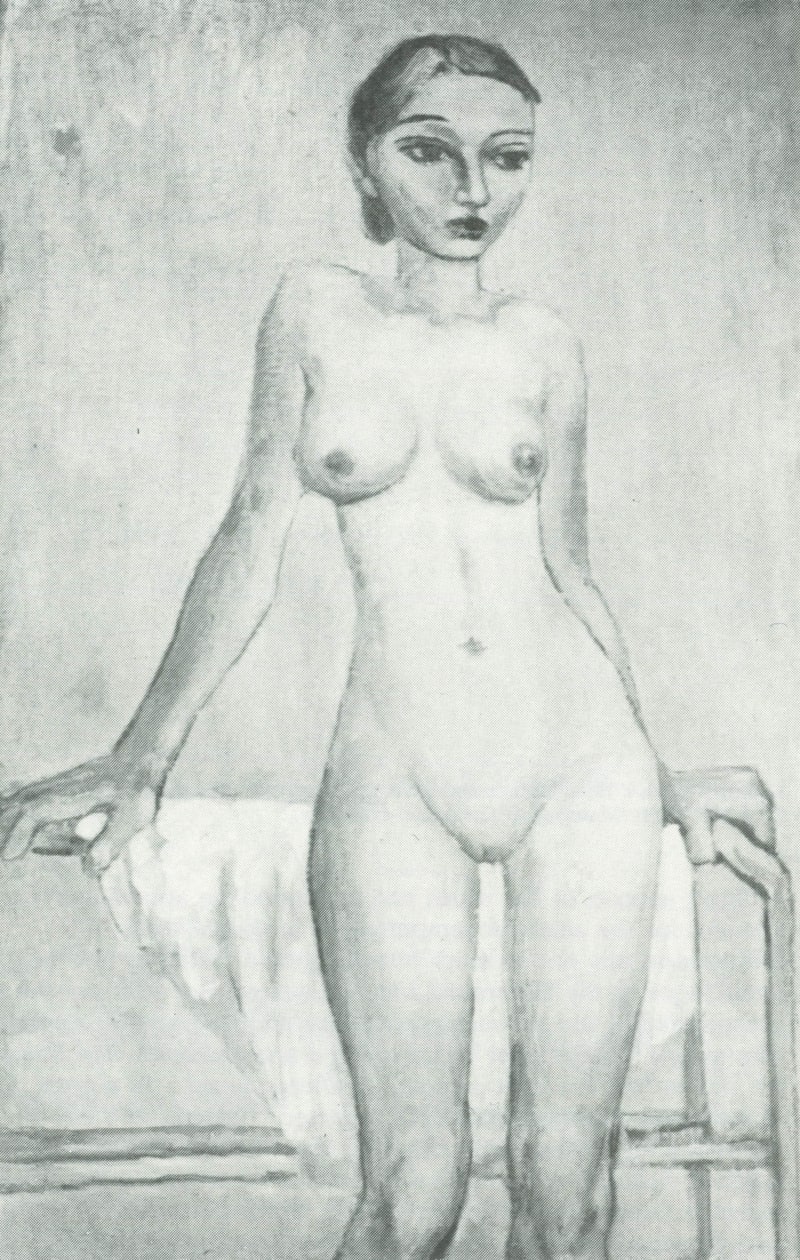

DARANIYAGALA: Nude. (Paris) Oil on canvas (60cm x 91.5cm). Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Toronto

Fred de Silva writing in the Times of Ceylon on the ‘43 Group’s ninth exhibition in 1954, found Daraniyagala’s work “most impressive, though a little hard of viewing. (It) seems to me to be technically proficient and rich in imaginative construction as any I have seen. A notable example of his now familiar evocative style is Girl with a Bull, a dramatic tonal essay on the subject of an earth-brown beauty and her electric-blue beast. The muted violence of this painting haunts one long after it is seen. “Nevertheless,” observed Fred de Silva, “much of his painting remains fiercely elusive.”

DARANIYAGALA: Mother and Child. Oil on canvas (77.5cm x 141cm). Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Toronto

Not so for Georges Besson. Writing with a fierce eloquence on the Petit Palais showing of the ‘43 Group in the 19 November 1953 issue of Les Lettres Francaises, he suggested “the French public will give their particular attention to the nineteen works of Justin Daraniyagala which are like fragments of a huge, monumental composition, bursting with life and bearing a very special kind of formal lyricism … This realist painter, this man of vision from Ceylon, with his extraordinary range of colour, this Daraniyagala, whose name we should all remember will be known from now on as one of the important revelations of our time.”

A comprehensive collection of his work to be put on permanent exhibition is as essential as any intelligent and sensitive conservation of Sri Lanka’s antiquities. What there remains of Daraniyagala’s work in the country is in need of immediate conservation, sometimes even of restoration, and public showing because they are part of the country’s inheritance.